Fieri has been putting together a new programme for our 2015 season over the past few months, and it’s proved a challenge. Several festivals at which we’ll be singing are going for themes related to ‘light’ this year, so we had a starting point; but to be perfectly honest, even this isn’t much help. Not because there’s a restricted amount of choral material on this subject, but because there’s such a vast array. Given the historic use of unaccompanied singing (in the Church, mostly), light absolutely abounds as a theme; in texts, in tunes, in inspiration. Whole schools of music were developed because of the gothic penchant for creating light-filled space (for those unfamiliar with the sinuous development of the word gothic, it used to have very different connotations from its present day usage).

The other challenge is that many of our peers have recently performed or recorded programmes on a similar theme, and whilst there’s nothing wrong with some flattering imitation, it’s also nice to discover a new strand to an idea. We spoke about the dichotomy of darkness and light, trying to turn it on its head; the comfort of darkness, the sometimes harsh nature of light. Gradually we found the direction we wanted to head in.

Sin and redemption, whilst touchy subjects, have inspired some of the greatest music ever composed; and of course, there are reams to choose from. In the end, the programme settled down around the music of Gesualdo, the murderous composer-Prince; some of the more exotic works of William Byrd; Orlando Lassus’ ‘Sibylline Prophecies’ (I have to thank my teacher Roderick for this discovery); and several of James Macmillan’s most arresting pieces. Really, each of these strands deserve (and perhaps will have) their own blog posts, but for now, I’d like to talk about about the most unfamiliar items in the programme: shape-note music.

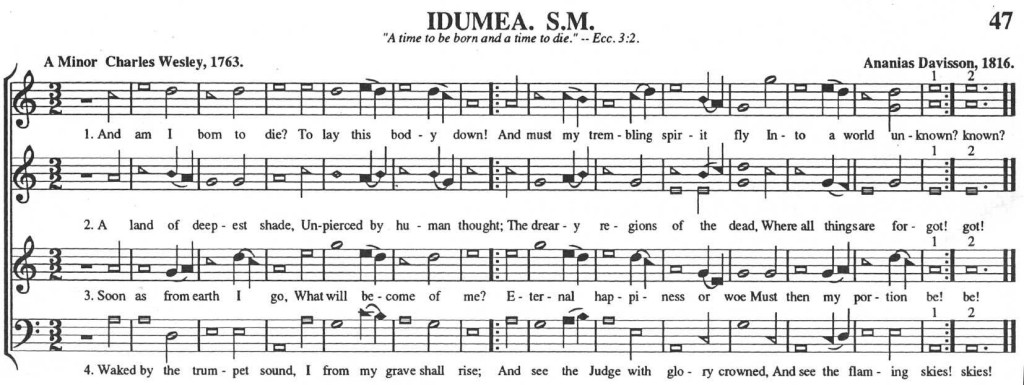

A form developed on the other side of the pond, shape-note singing is referred to as early as the late 18th century. The tunes used are much older than that however, and I suspect that several deserve the moniker of ‘early music’ even by European standards. The genre has a long and fascinating history, and many words have already been written about its development, so I’ll try not to add too much to that.

The notation was created as a teaching aid; by reinforcing the position of the note on the stave with shaped note-heads, the identification of scale degrees could be taught more quickly. The really interesting aspect, from a singer’s point of view, is not the novel notation, but the style of the singing. Hymns (both homophonic and in basic polyphony) are superimposed with a puritanical fervour which is recognisably and unashamedly American. The texts are harsh, with concepts that were gently dropped from British hymnody over successive generations; eternal damnation appears often. Delivery is not genteel and refined, as in the finely shaped and mannered interpretations of cathedral choirs, but loud and brash, with no attempt at phrasing. Artistry is not the point here. The singing is not for the benefit of an audience, or even a congregation, but for God and the singers themselves.

From the description above, it sounds as if the resulting sound should be an out-of-tune and abrasive mess; not so! In fact, the effect, for someone unfamiliar with the style, is chilling. The tone, forward and tenor-heavy, creates an otherworldly sound which emphasises the nature of the texts with perfect clarity. Personally speaking, I’m not used to the open chords, slightly alternative tuning and the sheer power characteristic of this style, and find it totally arresting. It makes me think of the motives of the early settlers, the nature of Christianity at that point in time; and with the benefit of hindsight, the roots of radical fundamentalism can be heard in the unrelenting onslaught of sound. There’s a reason this style persists mainly in the South – a reminder of the rotten core of the pioneer spirit and manifest destiny, based on an increasingly hypocritical moral framework which twists and decays, corrupted by a capitalism which treats men as property.

The words above may seem a little harsh, and indeed the performance of this music is not directly related to slavery. But the fact remains that these are the hymns which were sung in many American churches at a time when some of the most horrific abuses of human rights were occurring, and the association is hard to ignore. Some people refer to Sacred Harp singing as ‘white spirituals’ (The Sacred Harp is a book which collated and presented many early shape-note tunes from the Southern US).

With all this in mind, and knowing the context, I’m looking forward to singing them and exploring the unique aspects of this odd and somewhat anachronistic music. I’ll learn a little more next week, when I attend a singing of the London Sacred Harp group. It should be a fascinating experience.

I’ll leave you with an arrangement of the song shown throughout this post. It’s less raw than ‘real’ sacred harp singing, but just as beautiful in my opinion.

Leave a Reply